It is usually people would have good liver function without cirrhosis, and disease confined to one part of their liver, that are considered for liver resections – that’s surgery to remove the part of the liver with the tumour in it. If a person does have cirrhosis but it is not so severe, they might be able to have a small tumour removed. Patients with more severe liver cirrhosis and poor liver function might be considered for liver transplant if they have very early stage liver cancers. Typically this means one cancer less than 5 cm. If there is more than one cancer, none of these should be more than 3 cm. Liver transplant cannot be considered at all if a person's cancer has spread outside their liver, or into one of the blood vessels in the liver. This is because a transplant – which is a very big operation with lifelong drugs afterwards – does not cure the person. If cancers are larger, there is a much higher chance the cancer will come back and spread more rapidly after a transplant. People who are fit enough though, with early stage cancers, can be cured by surgery. If at all possible, these are the treatments we would like to be able to offer our patients.

Find out more about transplant here.

Find out more about resection here.

These are treatments we consider if there are just one or two or possibly three relatively small cancers in a person's liver, without any spread elsewhere, again – if a person is fit enough.

For a small cancer of up to 2cm, we like to consider a treatment called ablation. This involves putting a needle into the tumour and destroying it by heating it up, usually with microwaves. You need a radiologist to use ultrasound or a different type of imaging to make sure the needle is put in the right place. Sometimes the radiologists give the treatment. If the cancer is in an awkward spot, or with the bowel or the gall bladder for example, very close by, the surgeons are also involved and use keyhole or laparoscopic procedures to guide the treatment. People are usually asleep when they have this done. Cancers up to 2 cm can be very well treated by ablation and even cured. We still consider ablation for cancers up to 3 cm, but sometimes in combination with trans-arterial chemoembolization or TACE.

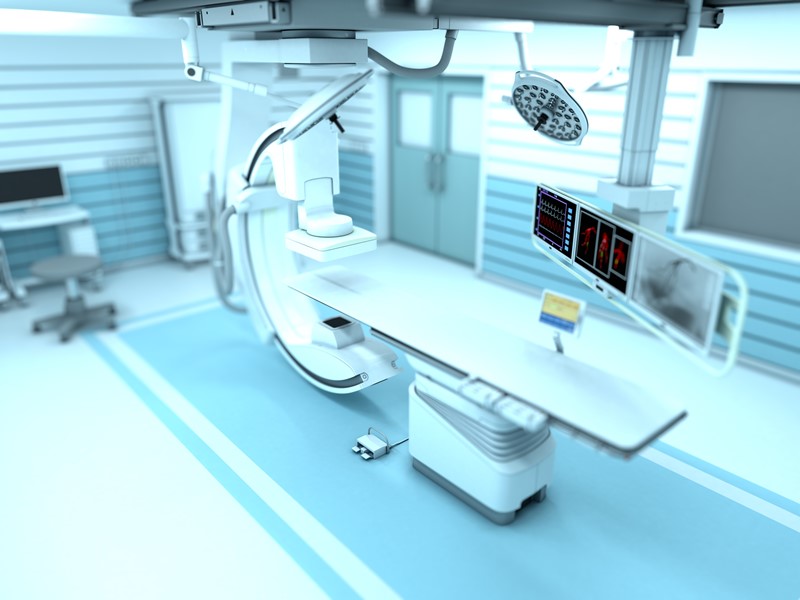

TACE is good for larger cancers, but ideally those that are not more than around 6 or 7cm. Our interventional radiologists give these too, in the radiology department. It relies on the radiologist being able to find the blood vessels that supply the tumour, to put treatment into the tumour and then block them off. The person is not put to sleep for it, but they have a local anaesthetic to numb the skin in the groin. Here, the radiologist will put a needle into the artery, and put in a fine plastic tube – called a catheter. The radiologist has imaging machines that move around to show where the tube is. They gently push it all the way up to the artery that supplies the liver. Then they inject a dye that shows up the blood vessels in the liver. This is called an angiogram. If they find the tumours blood supply, they inject the treatment.

Usually, after one of these treatments, the person would have a scan a month later to see how well it has worked. If it had worked really well we would probably do 3 monthly scans after that. This is called ‘active monitoring’, looking for any signs of recurrence. As time goes by, the frequency of the scans can be reduced. At least half the cancers do come back at some point – especially if they were larger or there was more than one. When that happens, we see if it is possible to give a loco-regional treatment again.

Find out more about TACE here.

Find out more about Ablation here.

A person who has a more advanced cancer at the time of their diagnosis, or a person whose cancer comes back after surgery or loco-regional treatments, may be referred to an oncologist to consider what we call ‘systemic treatment’. These are ones that will deliver a treatment to the whole ‘system’ or body. The advantage of them is that it can treat tumours in the liver, in the veins and outside the liver. They don’t often cure people, but they can slow down how quickly a cancer grows and significantly increase how long a person lives. Although they sometimes have side effects, these treatments don’t tend to carry the same risks as surgeries or loco-regional treatments. They are safer in people with symptoms from their disease. So its important not to keep going with other treatments, if they’re not working. We want as many of our patients as possible to still be fit enough, with good liver function, to have medical treatments when their cancers recur.

As recently as 10 years ago, there were no medical treatments proven to be any good in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma – the commonest primary liver cancer. But that has changed now. Sometimes the oncologist will advise a treatment called a ‘kinase inhibitor’. Sorafenib and Lenvatinib are kinase inhibitors. So is Regorafenib. There are newer treatments now, that switch on a persons’ immune system, to help it fight the cancer. These are called immuno-oncology treatments. There are also clinical trials of newer drugs or combinations of different drugs. For people who have a cholangiocarcinoma – this is one that starts in the bile ducts in a persons liver and is the second commonest cause of primary liver cancer, there are some different types of treatments that can also help. Your oncologist will very likely want you to have had or have a liver biopsy, to be sure about the type of cancer you have. With this, he/she will be able to talk to you about the different types of treatments and help decide if one of them is the right treatment for you.

Find out more about medical and oncology therapies here.